Celebrating SIU’s Saluki TRADITION, Saluki PRIDE and Saluki PROMISE for SIU’s 150thAnniversary, This Is SIU is publishing a monthly feature detailing the past, present and future of notable places, events and people on campus.

The tiny metal cannons he made for school history projects as a child were no bigger than a tooth. But that was the scale his father, a dentist, was set up to handle.

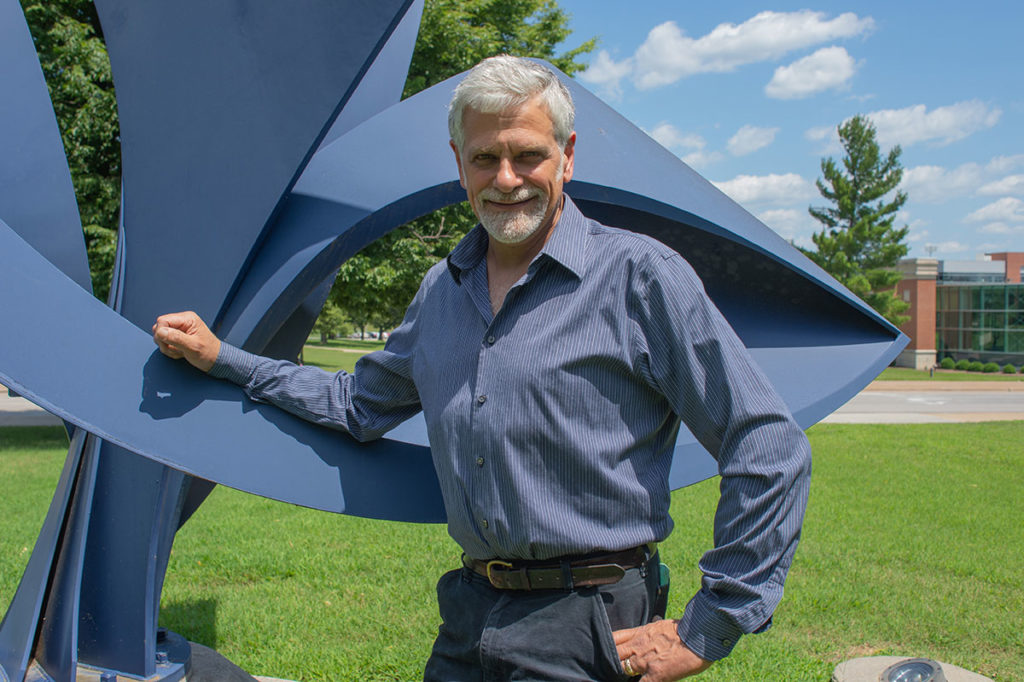

“I used the casting equipment in my dad’s office to make small sculptures when I was just a little kid, sometimes I cast my own tiny cannons for history dioramas,” said sculptor and metalsmith John Medwedeff, seated in his comfortable-but-crowded office loft above his Murphysboro studio. “I started making wire sculptures when I was about 9.”

As a child he worked in many media, but metal remained his favorite. Then at 10 years old, the budding artist had one of those moments that put him on the path in a more concrete way.

On a family trip to Michigan where his paternal grandfather worked as a top metallurgical engineer for an auto parts company, they explored Greenfield Village, part of The Henry Ford Museum. Among many other historic activities, craftsmen demonstrated the reemerging art of blacksmithing.

For Medwedeff, that really made the sparks fly.

“That was just seared into my mind,” said Medwedeff, who later worked his way to Southern Illinois University Carbondale’s metalsmithing program. “You have those moments when things come into focus, and for me one of the clearest was the first time I hit a hot piece of iron with a hammer. I knew I’d found my home. With the first hammer blow, I knew I had found my connection between metalsmithing and sculpture.”

Funny how something as small and delicate as those tooth-sized cannon would eventually lead to enormous works of public art on college campuses, river fronts and downtowns across the country. And for SIU, Medwedeff’s work in particular reflects the past, present and future.

Past, present and future

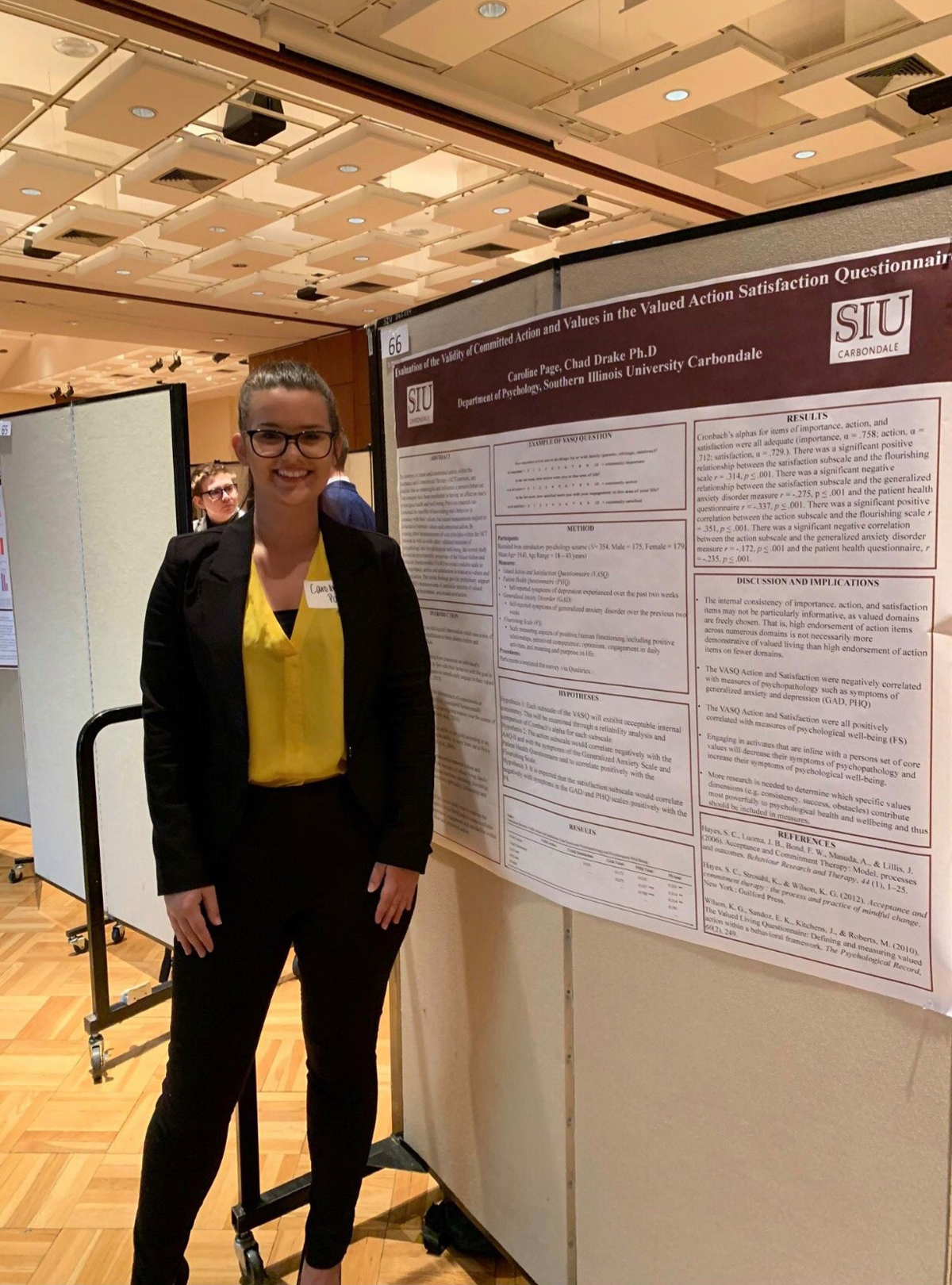

For SIU students and staff, and members of the Southern Illinois community in general, Medwedeff’s work is part of the very fabric of life. His enormous and graceful metal sculpture titled “Momentum” adorns the northeast corner of campus’ Engineering Building, while another, earlier work – “Combustion” – resides in the Communications Building.

Two more Medwedeff works are in the pipeline for SIU, as well. After a delay precipitated by the state budget standoff, another large steel sculpture is slated for installation at the Transportation Education Center at Southern Illinois Airport in 2020. The form is an attempt to capture the power, grace and artistry of flight and movement.

The other sculpture now in the works, commissioned by the SIU Alumni Association, marks a different artistic approach than the organic-inspired abstract sculptures he is known for creating. In celebration of its 150th anniversary, Medwedeff, working in collaboration with Medwedeff Forge & Design Studio Supervisor Megan Robin-Abbott, has realistically sculpted three larger-than-life saluki dogs, frozen in breathtaking motion. A part of the new Saluki Alumni Plaza, the dogs represent the past, present and future of the university.

Much like the sculpture, Medwedeff himself has experienced SIU in those three phases, too, starting as an apprentice to an alumni of what was then a relatively young metalsmithing program.

Artistic origins

Art positively inundated the Medwedeff household, as well as the family tree. His mother, who painted and made figurative sculpture, set aside a room in the house for him and his sisters to create art projects. His maternal grandfather, a doctor by profession, was a skilled furniture builder.

During those early years growing up in Nashville, Tennessee, Medwedeff also would find himself in the thrall of Christine Tibbot, a prolific and locally famous artist. Both he and his future wife, Cynthia Roth (also growing up in Nashville) took art lessons on Saturdays. Tibbot taught her students to create and think like artists.

“Christine Tibbot was one of the most creative, dynamic, energetic people I’ve ever known,” Medwedeff said. “She influenced a generation of kids in Nashville to become professional artists.”

As he reached 18, however, Medwedeff wasn’t sure how he fit into the artistic world. Following the example of his oldest sister, he enrolled at the Memphis Academy of Arts, where he planned to study graphic design in preparation for a possible career in commercial advertising.

He soon met Jim Wallace, a 1977 SIU alumnus and the founding director of the Metal Museum in Memphis. Medwedeff started his apprenticeship at the Metal Museum in 1982, developing his skills under Wallace’s direction until 1985.

Wallace had earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from SIU’s blacksmithing program started by L. Brent Kington in 1969. In the decades following its founding, Kington would lead the program to international prominence in the field of metalsmithing.

The program launched the careers of dozens of highly skilled artisans schooled in the art of heating, hammering and twisting metal into works of museum quality and architectural splendor. Along the way, Kington also made a national name for himself both as artist and teacher before retiring in 1997. Medwedeff is one of many professional metalsmiths who can trace their roots back to Carbondale.

“Brent’s contribution was bringing blacksmithing into the academic setting,” according to Medwedeff.

Becoming a Saluki

The blacksmithing craft, interrupted by the Great Depression, World War II, and the post war shift toward modernism, had lost continuity and tradition.

“A whole generation had been missed in this country, all the skills were very nearly lost. All but extinct,” Medwedeff said.

But blacksmithing was making a comeback, thanks to the work of a handful of artisans around the country and a cultural awakening among the younger generation. Initially World War II veterans, who turned to arts and crafts for therapy as much a practicality, started to investigate traditional crafts and in response universities began to offer classes in ceramics, glass, fiber, and jewelry. Outside of academia, the Fox Fire book series inspired the first wave of the Boomer generation to explore blacksmithing.

Kington saw something in Medwedeff that caused him to offer a scholarship. Not quite finished with his undergrad degree in Memphis, Medwedeff transferred to SIUC to study under Kington and Richard Maudsley.

“So SIU became this incubator in the 1970s to research these arts,” Medwedeff said. “I feel very lucky to have been at the crossroads of sculpture and blacksmithing. If I had not studied with Jim Wallace and come to SIU, I’m sure I would have ended up a sculptor, but would I had been a blacksmith as well as sculptor? I don’t know. And those two things together is kind of what puts a stamp on my work.”

That first big break

When he came to SIU at the tail end of his career as an undergraduate, Medwedeff couldn’t have imagined Southern Illinois would become his home for decades. A series of events led to him sinking deep roots here, where artistic synergies run strong.

He had earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in metalsmithing in 1986. As he was finishing up his Master of Fine Arts degree at SIU in 1988, the young artist opened a studio in part of the former Brown Shoe Co. factory in nearby Murphysboro. There, he eked out a living doing ornamental metalwork.

“Of course this was the pre-internet, almost pre-fax machine days and things were pretty lean,” he said. “I made stuff like coffee tables and small projects. My goal was to make sculpture but I hadn’t yet figured out how to make that economically viable.”

A good break came in 1990, when Wallace put him touch with the designers of impressive home being renovated in St. Louis. It led to a long-term association with New York-based architects and interior designers, including Jed Johnson, who sent him a steady stream of high-end traditional style metalwork commissions for their clients.

Medwedeff was grateful for the economic stability it brought him. But his desire to sculpt in metal burned brighter than ever.

“I remember thinking I was getting somewhat pigeon-holed in this area,” he said. “Right around that time, I was asked to submit a design for a gate or ceremonial arch at the Illinois State Fairgrounds in Springfield, and I thought to myself, ‘It’s time to roll the dice,’ and I submitted a design that was in no way a traditional piece of iron work. Structurally it was an arch, but aesthetically it was sculpture.”

He unanimously won the competition, which is when Medwedeff – who was elated – also realized he’d set out quite a challenge for himself.

“My shop at the time had 11-foot ceilings and the piece I designed was 26 feet tall,” he said. “But that’s how I did things early on. I’d just make the design and figure out how to build it later.

“I’ve gotten better about that over the years,” he added.

SIU boasts several Medwedeff works

That first public art commission is the hardest one to get. And sure enough, once the flood gates opened Medwedeff found himself hustling to keep up. Bigger digs were needed, so he bought an existing metal building with a 37-foot-high ceiling from a coal mine in Benton, Illinois, disassembled it and rebuilt it at its current site in the Murphysboro Industrial Park where it serves as his studio.

It wasn’t long before his alma mater came calling, as well. An early public art project is “Combustion,” which hangs in the Communications Building. In 2004, he created “Momentum,” a fabricated steel structure installed on the northeast corner of SIU’s Engineering Building.

“It’s at the Engineering Building, so the concept I started with are the principles of structural engineering. The piece derives its strength from opposing compound curves in the surfaces. That main form that sweeps around the core of the sculpture is kind of like an I-beam but the web and the flange trade places. Engineers have charts for structural properties of beams, but there’s no chart for what I do. So I’m challenging the notions of standard engineering, although all the rules apply.”

Soon to adorn the north entrance of SIU’s Transportation Education Center is a very large piece which calls on esoteric notions of travel such as speed, power and acceleration.

“I had just visited the new Air & Space Museum at the Smithsonian when I designed this sculpture. They have an aircraft there, the SR-71 Blackbird, and it really knocked me out with its shape,” he said. “One of my assistants was a jet engine mechanic in the Illinois Air National Guard, so I had learned a lot from him about how jets are put together and work. I was going for the essence of movement and things that go fast.”

The sculpture for the new Saluki Alumni Plaza represents a major departure for Medwedeff Forge & Design, in that it is representational figurative sculpture. He, Robin-Abbott and their assistant Gabriel Chaille sculpted the three dogs using epoxy modeling compounds and foam before shipping them in July to a foundry in Ohio where the artwork will be cast in bronze.

The pieces is scheduled for installation at the new Saluki Alumni Plaza, located between Pulliam and Woody halls, early next year as part of the university’s 150th anniversary celebration.

Southern Illinois and well beyond

Medwedeff’s sculptures today are located from coast to coast in United States. The farthest away are installed in Washington State, Michigan, and most of the southeastern states. In 2017 he collaborated with another SIU Metals Program alumni, Erika Strecker, to create a major sculpture installation inside the University of Kentucky Children’s Hospital.

Closer to home, his touch can be seen at Carbondale Community High School, as well as the design of the Towne Center Park landscaping, band shell, and fountain and the Smysor Plaza fountain in Murphysboro.

Medwedeff said staying in Southern Illinois and close to SIU has paid off in many ways, from hiring skilled, motivated young artists from the SIU metalsmithing and sculpture programs just down the road, to having key contacts that have helped him in business along the way. Having his art on permanent display at SIU is a special thrill.

“These pieces will be here a long time, and public art can be enjoyed by everyone, regardless of their economic stature,” he said. “Works like these provide a psychological landmark in their lives – people do things like have their wedding and graduation pictures taken with them. I really enjoy that.”