Sometimes new discoveries come wrapped in, well, not the most attractive packages.

Behold, the aptly named naked mole-rat.

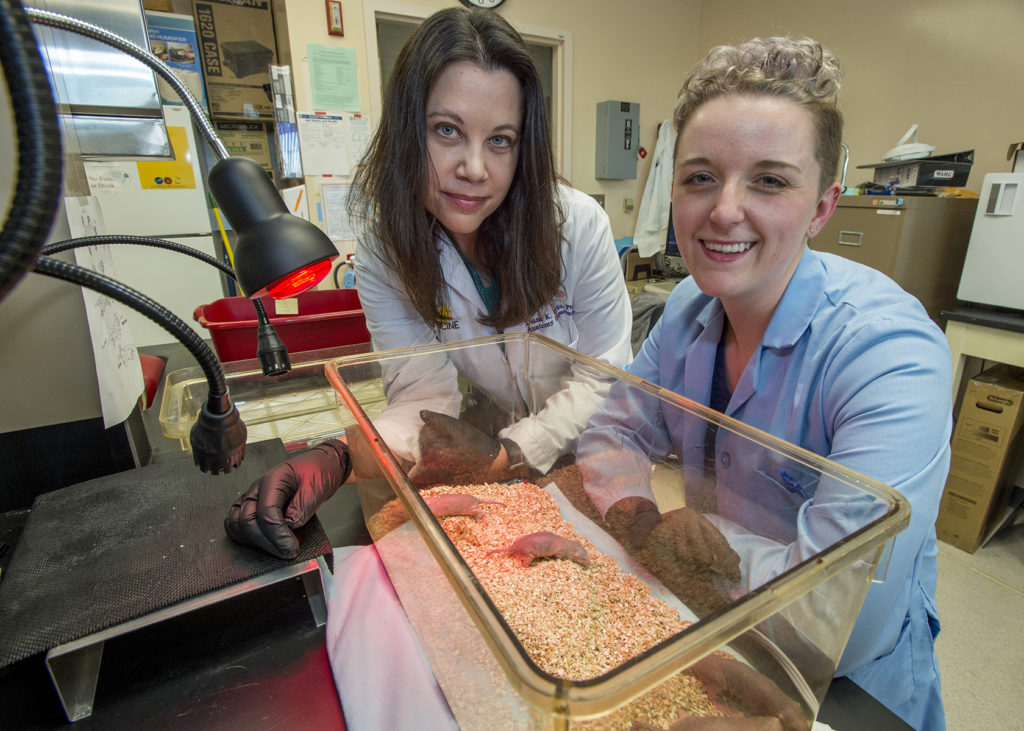

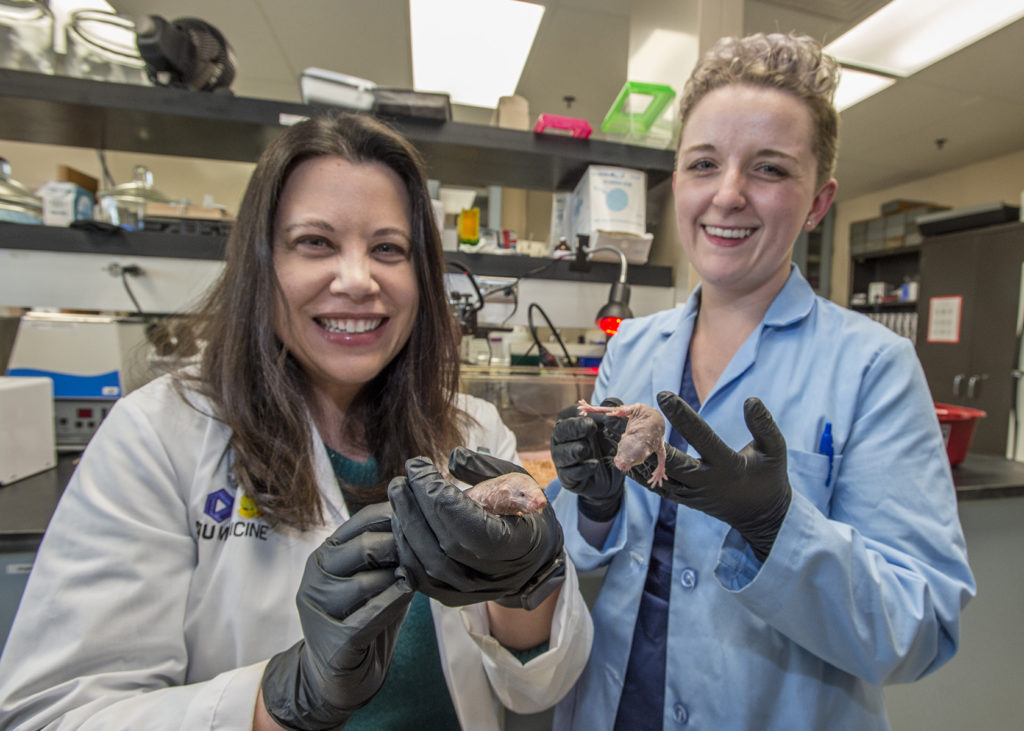

Diana Sarko, assistant professor of anatomy in the SIU School of Medicine, holds a naked mole-rat in her laboratory at SIU Carbondale. Sarko and her doctoral student, Natalee Hite, found that subordinate animals within the colony have the strongest bite force, which flies in the face of most other mammalian species, where the largest animals bite the hardest. (Photos by Russell Bailey)

The east African rodent probably won’t win any prizes for its cute quotient, but the way its society is structured within its underground colonies is fascinating and unique among mammals. And its incredibly long life (for a rodent) and practically non-existent cancer rates make it a great model animal for scientists studying aging and disease among humans.

SIU researchers unveil findings

Researchers at SIU Carbondale recently published a paper on the animal after discovering another interesting difference between it and other creatures having to do with how hard it bites. Not only does the naked mole-rat “punch above its weight” in this area, but the amount of force it exerts is linked to its social status within the colony.

The research conducted by Diana Sarko, assistant professor of anatomy in the SIU School of Medicine, along with her doctoral student, Natalee Hite, found that subordinate animals within the colony have the strongest bite force, which flies in the face of most other mammalian species, where the largest animals bite the hardest.

Small, but mighty

Weighing in at less than 2 ounces, and measuring just 3 to 4 inches long on average, naked mole-rats live in groups inside burrows. Its weird combination of unusual characteristics allow it to flourish in such harsh environments.

Their skin lacks sensitivity to pain and they can live up to 30 years, far beyond the normal lifespan of their cousins in the rodent family. Their outsized incisors are wired for touch, taking up a great portion of their brain’s tactile processing region. Not only do they use the teeth for defense, but also use them to feel their way through the dark, subterranean labyrinths they call home.

A commonality with bees

But one of the most unique characteristics are their social hierarchies. Naked mole-rats are eusocial, meaning that, not unlike bees, each colony has a “queen” along with dominant and subordinate members. The animal is the only known mammal to use such a social structure.

In this structure, only the queen and a select group of males reproduce, with the rest of the colony acting as reproductively suppressed “workers,’ both male and female, whose job is defending, maintaining and expanding the structure of the burrows, and caring for the pups produced by the reproducing female.

“This is the first study to show a relationship between bite strength and social status in naked mole-rats,” said Sarko, a neuroscientist who is interested in studying sensory systems, including unusual sensory adaptations and the plasticity of sensory systems. “It was a surprise because across a wide range of species that have been studied by other researchers, the general rule is that the bigger you are, the harder you bite.”

Seeing the potential

Sarko first began studying the animals as a post-doctoral researcher at Vanderbilt University. She quickly learned that strange combination of traits make naked mole-rats a useful analog for human anatomy.

“The fact that they have a long lifespan, and that they live that long without getting cancer make them a desirable model for aging and cancer studies,” she said. “Their large, specialized incisors make them a great model for studying tactile inputs from the teeth, as well as sensory reorganization following tooth loss. And tooth loss is a critical issue for human health, affecting the diet and self-image of a large percentage of adults in the U.S.”

Testing theories, finding surprises

Along with Hite, Sarko worked with two colonies and a total of 60 animals. One at a time, they tested each animal by bringing them up to the lab, placing them in chambers similar to their housing chambers and presenting them with a bite-force sensor.

Each animal was free to interact with the bite-force sensor for approximately 20 minutes before being returned to their home cages of their colony. The force sensor was connected to a small computer running customized software to record any force applied to it.

The research was conducted at SIU Carbondale over the last two years.

Asking why

The researchers’ findings were published in December in the journal Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. Sarko and Hite theorize that the difference in bite force among the animals may be somewhat impacted by their varying roles in the social structure.

“Subordinates take on the role of colony defense, which might require stronger bites, whereas dominant animals have already established their positions within the colony and may be ‘resting on their laurels’ a bit, not needing to further prove themselves,” Sarko said. The two researchers studied colonies that already had well established social hierarchies. An interesting next step might be to introduce changes in the system, such as studying the possibly changing bite force of subordinate animals as it transitions into a dominant position.