Although it produces a needed product, a strip mine can lay waste to large areas of land, making them unfit for wildlife for years to come, unless steps are taken to restore them.

Burning Star No. 5, located on thousands of acres of rolling hills, tall grass, farm fields, woods and ponds near De Soto, is no exception. And a student in the zoology degree program at Southern Illinois University Carbondale is spending many hours combing through the area to find out just how successful grassland restoration in the area has become.

Alexander Glass, a doctoral student with SIU’s Cooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory, has spent the last 12 months researching the impact of restoration efforts on grassland birds, arthropods, small mammals, pollinators and snakes.

Working with Michael Eichholz, associate professor of zoology, Glass spent May through July collecting specimens and making observations at the site in an effort to paint a broader, more complete picture of how the area’s wildlife comeback is progressing.

“This project is important, and pretty unique, because of its holistic approach,” said Glass, who came to SIU to pursue a career as wildlife biologist after spending time banding and studying grassland birds in southeastern Nebraska.

Study aims for the big picture

Although scientists have long studied how different land management and restoration efforts affect wildlife, most studies are narrow in scope. But such areas maintain species that are quite dynamic and interrelated in how they interact, so Glass is trying to capture more of a big picture perspective on the situation.

“An in-depth answer to this question involves not only understanding how grassland birds respond to management actions, but also the responses of nest predators, prey and vegetation structure and composition,” he said. “Understanding all these interactions will help explain why grassland birds react to management actions the way they do, which can lead to more informed management decisions.”

Big task requires multifaceted approach.

Glass and others worked in the field throughout the grassland birds breeding season, spending six days a week making various observations. A large portion of the time was spend searching for nests by dragging a rope across the tall grass in an effort to flush the birds.

“Grassland birds usually nest close to the ground in vegetation clumps. We monitor all the nests we find by checking them every three to five days until they hatch or are predated,” Glass said.

He and the crew also estimate the abundance of small mammals such as field mice at each of their nine designated sites by setting out baited, live traps, checking them regularly and marking captured specimens with ear tags. Medium-sized mammals are counted using trail cameras and baits, allowing the researchers to estimate their population, as well.

They also estimate the biomass and diversity of the arthropod population – spiders and other insects, essentially – by catching them in traps for later analysis in the lab.

To study the snake population, the researchers set out grid of 20 “coverboards” – plywood sheets that cover one square meter – and then simply check underneath once a week, recording what types they find.

Lastly, the researchers measure vegetation structure – its height, density, different types and composition – along a 100-meter line that transects on each of the nine sites.

Lab work continues

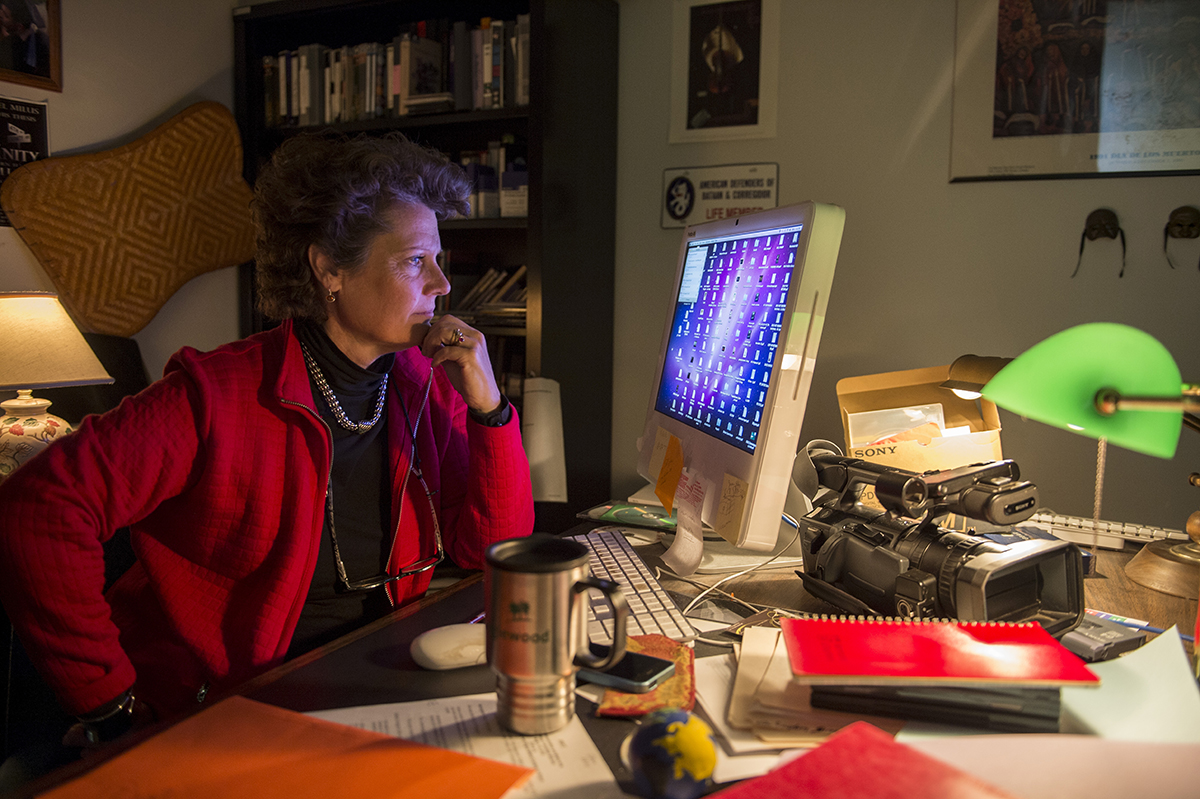

With fall approaching, the research has moved indoors to the lab, where Glass spends time identifying and weighing specimens from the field and doing other analysis.

“My career goal is to become a research biologist and work to improve land management practices and conservation efforts for species of concern,” he said. “This project is a huge step in that direction, since it gives me valuable experience designing and implementing a field study that asks important questions relevant to my interests.”