When it comes identifying cougars, sometimes you can’t believe your eyes.

That is to say, people often mistakenly identify photos other creatures – bobcats, house cats, dogs and other species – as cougars.

The problem of misidentification is prevalent enough that The Cougar Network, a nonprofit research organization dedicated to studying cougar habitat and the role of cougars in ecosystems, runs a popular weekly feature called #CougarOrNot on Twitter. The polling-style game that’s been around since fall of 2015 involves posting a photo each Friday and then inviting participants to identify the beast as a cougar … or not a cougar.

Accuracy counts

A graduate student at Southern Illinois University Carbondale is working with researchers to find out just how accurate – or inaccurate – the public is in identifying cougars in the #CougarOrNot photos. Her findings might tell scientists whether they can rely on visual sightings alone of a cougar’s presence, even as the great cat’s range continues to grow.

“The cougars’ range is expanding eastward, and tracking cougars is more important now than ever before,” said Kori Kirkpatrick, who is earning a master’s degree in zoology.

Kirkpatrick is also investigating whether online games such as #CougarOrNot improve the public’s accuracy.

“Maybe activities like this are a way to allow for visual sightings to be more reliable,” said Kirkpatrick, who started working on the project last fall.

That’s important, because researchers and organizations such as The Cougar Network are being flooded with alleged sightings in the form of photographs, tracks, scat and simple visual sightings. Researchers tend to discount visual sightings, as there typically is no objective evidence to verify them.

Can social media boost science?

Getting a handle on how well the public visually identify cougars could change that, and potentially provide researchers with an army of observers to help track the cougars’ expansion.

“I want to know if visual sightings have enough accuracy to be used, and if things like demographics of the person identifying affect the accuracy.”

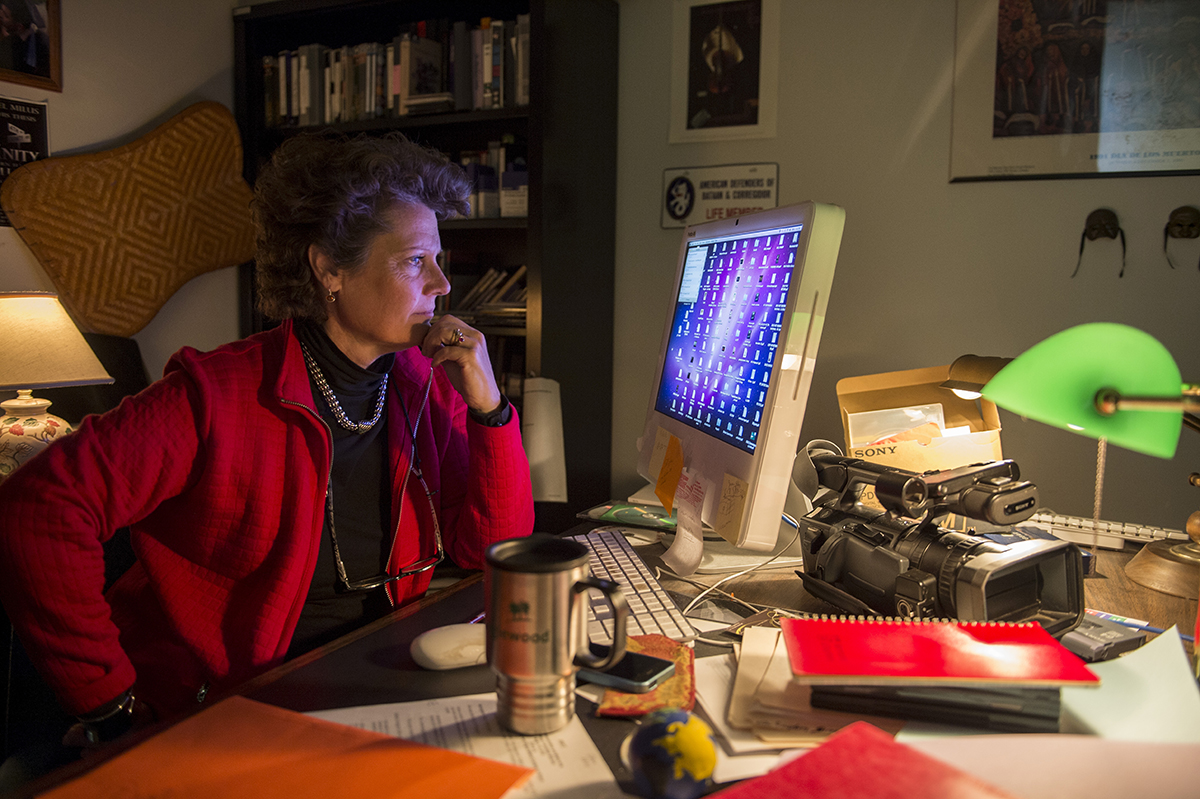

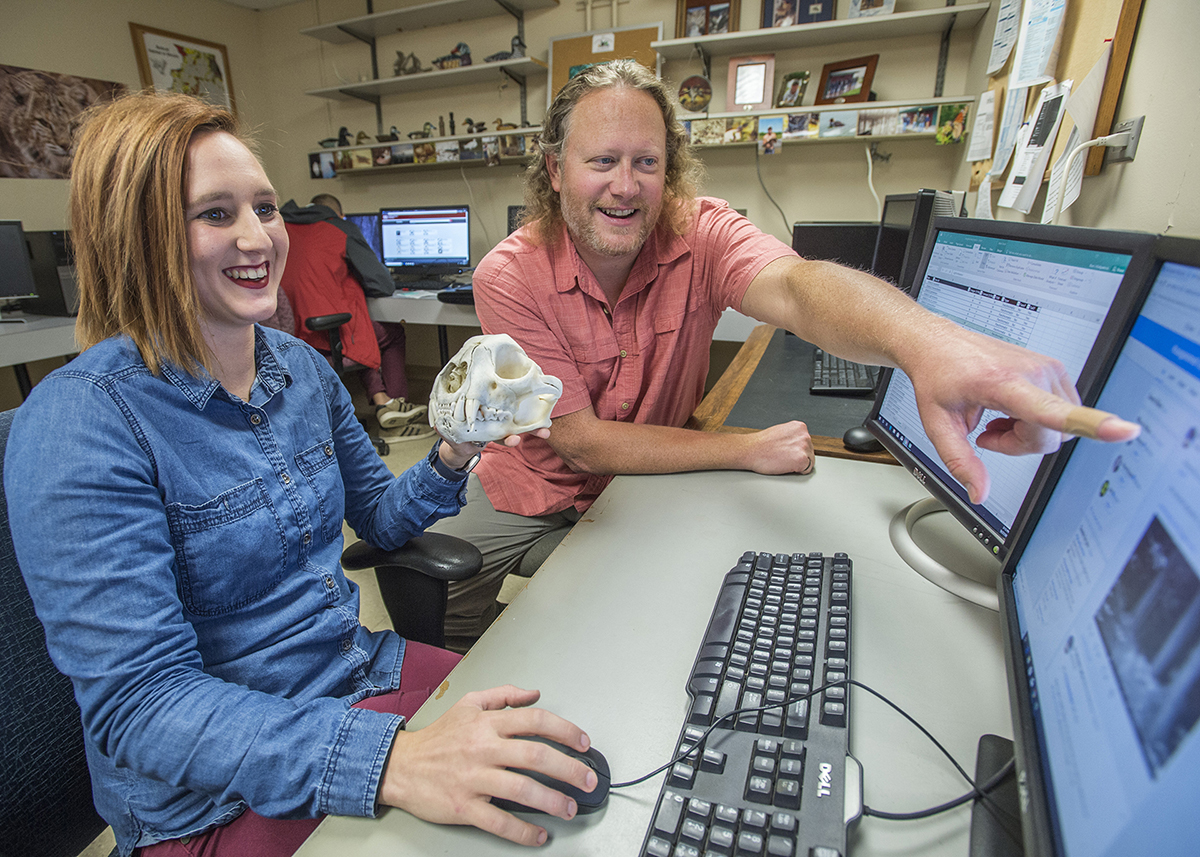

Working with Michelle LaRue, an SIU assistant scientist who is also executive director of The Cougar Network, and Clay Nielsen, a professor of wildlife ecology and conservation in the forestry degree program, Kirkpatrick is surveying participants in #CougarOrNot to evaluate the accuracy of photo identifications, to understand demographic characteristics of participants who offer the most accurate sightings and to determine whether #CougarOrNot responses increase in accuracy over time.

Demographics might play a role

Kirkpatrick, who is receiving partial funding for the study from The Cougar Network, expects the simple, 5-minute online surveys to tell a lot about cougar enthusiasts.

“Factors such as location, education and age have been show to affect people’s perceptions. I believe they will also affect a person’s ability to correctly identify cougars,” she said. “By knowing whether this is true, we can look at visual sighting information more accurately,” by assigning more weight to sightings by people from certain demographic groups that prove to be more accurate.

SIU’s Nielsen and others continue to break ground

Overseeing the project is Nielsen, whose research group has studied Midwest cougar recolonization for 15 years, publishing multiple papers on topics such as potential cougar habitat, future population levels and human dimensions. As a leader in this area of research, Nielsen sees the #CougarOrNot project as an extension of that previous work, providing further understanding of the human element in large carnivore recolonization.

“This project is important because it investigates the potential role of social media in assisting with large carnivore conservation efforts,” said Nielsen, adding that such research is rare in the scientific literature. “Kori was a perfect choice for this work given her passion for carnivore conservation and prior excellence as an undergraduate student at SIU who also had already worked in my research group.”

A life-long fascination, new scientific tools

For Kirkpatrick, researching cougars is a passion that started when she was an elementary school student. Working in Nielsen’s lab as an undergraduate led to working with LaRue and the Cougar Network, where the trio came up with the idea for the survey project that could also serve as master’s thesis.

“As I have delved deeper into this project, I have been fascinated with the concept of combining social media with conservation science,” Kirkpatrick said. “It’s a partnership of two fields that many in the conservation realm believe to be contradictory. But using social media can only improve the methods of conservation science, and I look forward to seeing how it can expand.”

Since its founding in 2002, The Cougar Network has compiled more than 900 confirmations of cougars outside its established range in the North American west. It seeks continuing input from our network, state and federal agencies and the public.

“I hope to answer the question of how reliable visual sighting data is for cougars, as well as create a method for other researchers to answer the same question with their own species they are researching,” Kirkpatrick said. “I also hope to highlight the important contribution that social media can make to science education and outreach, as well as a method for data collection and citizen science.”